The Design Lifecycle

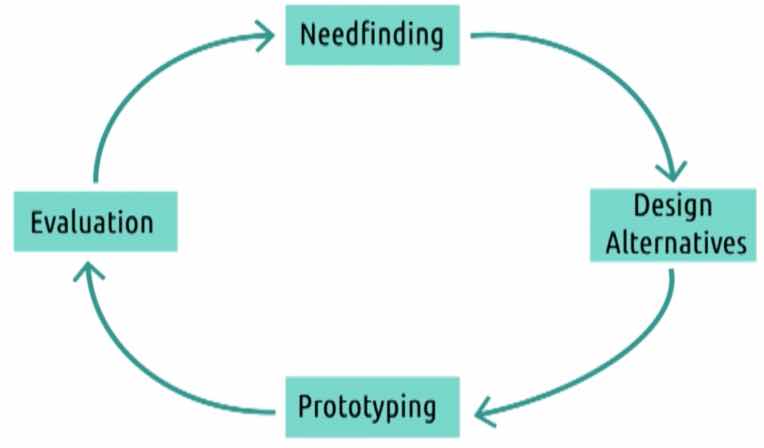

A topic covered in my Human Computer Interaction course was the design lifecycle. This process helps you to prioritize user needs, even though you may not know what those needs are, while prototyping ideas for a new interface.

The design lifecycle has four steps which form a feedback loop. This loop helps you learn about your users, and narrow in on design alternatives that serve users best for the task at hand.

Starting at the top:

Needfinding

Needfinding focuses on learning information about your users: who they are, why they need to accomplish the task for which you are designing, and how they currently accomplish it.

Needfinding often involves real user participation via in person interviews or surveys, but can also be done by analyzing reviews of similar products (to understand gaps in other offerings) or through “naturalistic observation” where you observe users in the context of the task.

Needfinding aims to fill a data inventory that describes the who, what, where, and why questions about your users and their tasks. Each time you perform needfinding, you should be adding additional information to each of these inventory items so you get a clearer picture of your users over time.

The items in your data inventory are:

- Who are the users

- what are their ages, genders, technical ability, etc…

- Where are the users

- where do they exist physically?

- What is the context of the task

- what else is competing for their attention?

- What are their goals

- what are they trying to accomplish?

- What do they need

- what are the physical objects, information do they need?

- What are their tasks

- what are they doing physically, cognitively, socially?

- What are their subtasks

- how do they accomplish those subtasks?

Design Alternatives

After we learn about our users via needfinding, we take that information and start to brainstorm potential solutions to satisfy the problems of these users.

The goal of this step is to generate lots of ideas. No idea is too crazy, as every idea help us to explore more of the potential design space for the target task.

Brainstorming as a group is helpful, since different people will look at a problem from different perspectives, but it is often useful to perform a round of individual brainstorming so you don’t fall trap to some of the pitfalls of group brainstorming (like social loafing, conformity, production matching, and performance matching / biases).

I found it useful to use a digital tool like funretro.io to keep track of ideas while brainstorming. This collaborative tool allowed multiple people to chime in with comments and new ideas, making for a more successful brainstorming session overall.

It is important to narrow your design alternatives down to the most viable ones by the time you exit brainstorming. Keep every idea that was generated, but choose a couple to focus on for the next stage of the design lifecycle.

Prototyping

After deciding on a few design alternatives that came out of brainstorming, we move on to prototyping some of those ideas out.

Prototypes can take many forms, on a range from lo-fi (paper prototypes, text prototypes) to hi-fi (interactive wireframes).

The fidelity of a prototype elicits different responses from users who evaluate them:

-

If an idea is still in its infancy, a lo-fi prototype is often more appropriate since it causes users to focus more on the mechanics of the task at hand instead of implementation details about the prototype.

-

If an idea is more fleshed out, and you’re looking for targeted feedback about the implementation of a design alternative, a hi-fi prototype is your best bet.

Hi-fi prototypes are more expensive to build, so often it’s better to start with a lo-fi prototype to validate that the design alternative is sound before moving on to more targeted hi-fi feedback.

Evaluation

After building a prototype for a design alternative, we move on to the evaluation phase where we get that prototype in the hands of some real users to get feedback and validate our ideas.

There are three types of evaluation that we can perform on our prototypes:

-

Qualitative Evaluation - This style of evaluation helps understand what users like and dislike about a design alternative by allowing them to express freely their thoughts and feelings. By performing interviews, giving surveys, conducting focus groups… we can understand what our users find easy, difficult, and confusing about a prototype. This type of evaluation is often conducted on lo-fi prototypes.

-

Empirical Evaluation - This kind of evaluation generates quantitative data that help us validate via statistical methods whether our prototype is objectively “better” than alternatives. Quantitative studies are often more rigorously designed, but result in stronger conclusions about the performance of our design alternative. Empirical evaluation is often performed on hi-fi prototypes, since it would be difficult to collect high quality data on anything less.

-

Predictive Evaluation - This evaluation method requires no additional user involvement. Instead, the evaluator (you) attempts to put themselves in the shoes of their users, and produce similar data to what a user might provide you. This type of evaluation is useful when we don’t have access to our target users, or if we want to iterate more quickly.

What Happens Next?

After conducting our evaluation, we decide if our data was conclusive enough to move our prototype through to full implementation. If we aren’t convinced, or if the data was inconclusive, we can iterate through the design lifecycle once again starting with needfinding.

All of the information we collected from the first round of the design lifecycle sticks with us, though, and informs us during the next iteration. For example, maybe we realized we need to know a bit more about the users’ context while they are performing the target task: we can target our needfinding exercise to elicit this type of information. This might prompt us to brainstorm design alternatives from a different angle, and come up with better prototypes that resonate more with our users.

It’s a virtuous cycle that brings us closer to an optimal interface that solves our users’ task with each loop.

Comments